The collective trauma of the global flood

For several thousand years, all of humanity has had a very serious psychological problem. We suffer from collective trauma after the extremely dramatic events that accompanied the birth of our own Species [I reported on this in the previous post (UP. 37) of this blog.]. To address the problem scientifically, I am basing my comments here on the latest book by psychotherapy specialist Dr Maggie Schauer [Maggie Schauer and Nataly Bleuel, ‘The Simplest Psychotherapy in the World; How We Treat the Cause of Stress and Illness and Break the Cycle of Trauma and Violence’ (Rowohlt, Hamburg, September 2024).]. Although she claims in her book [Schauer and Bleuel; p.141.] that ‘In its essence, narrative exposure therapy is by far the simplest psychotherapy in the world,’ I quote (in the appendix) several fragments directly from this specialist book so that we actually remain on a solid scientific basis in this article.

To explain our assertion of the transgenerational trauma of all of humanity, we will begin by taking a closer look at an example from the authors [Schauer and Bleuel; p.143.] from 20th-century German history.

‘For we must expect that the effects of important events that took place in the past in the family of origin, in the tribe or in the group will also make themselves felt in the childhood and adulthood of subsequent generations.

Many of the baby boomers in Germany, the ‘war grandchildren’, who were indirectly traumatised by the unresolved psychological traumas of their ancestors, were unable to really reach their parents emotionally and describe fears that they cannot explain by their own biography. And yet the painful experiences of that time were very specifically evident in the impatience, anger and psychological stress of the parents in their daily lives. The past impacts the present again. Individual and transgenerational suffering from the reactions and consequential symptoms of traumatising life events can be treated. Storytelling as a fundamental traditional cultural practice contains healing knowledge and has shown promising treatment results. As a biographical tool, narrative exposure has the potential to influence areas as diverse as psychotherapy, basic psychosomatic care and the contemporary practice of general practitioners, as well as other social and health care professions such as social work and trauma education.’

Let us repeat the sentence highlighted in bold from this quote: ‘The past impacts the present again.’ This is our explanation of the traumatising role of the greatest catastrophe of humanity in our shared life to this day, several thousand years after the actual catastrophe. And we are trying, for the first time in our history, to use the potential of narrative exposure to initiate a healing of our collective post-traumatic disorder. To do this, however, we must actually and seriously perceive (and not just want to perceive!) that the trauma we are describing here has not only connected individual generations of those affected, but has affected all of our generations of the Species Homo sapiens Sapiens, since the time when the last Neanderthals left the Earth. To do this, we ask some important questions that we try to answer with the new tools of our Unified Science, especially Universal Philosophy. At the end of the article, we find the relevant statements by the authors of the above-mentioned book.

Question 1: Why has it been impossible to study the history of humanity over the last 12,000 years?

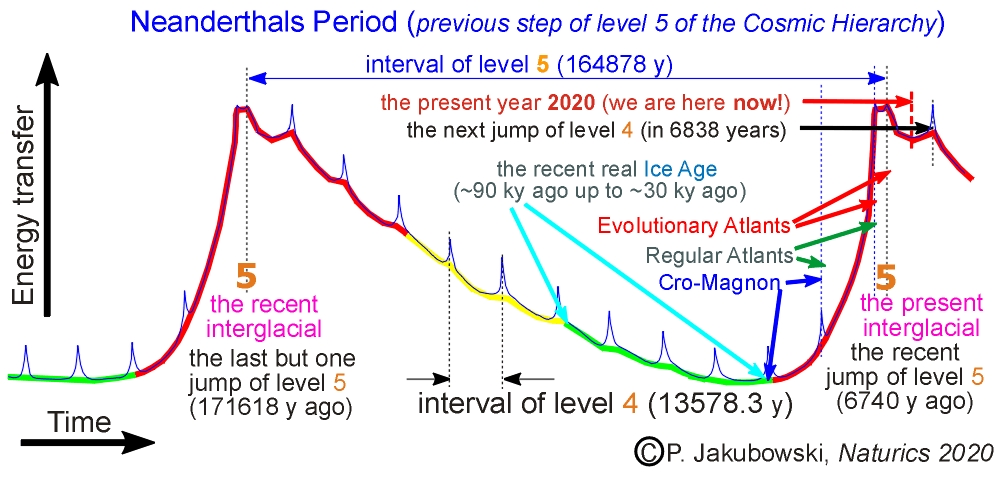

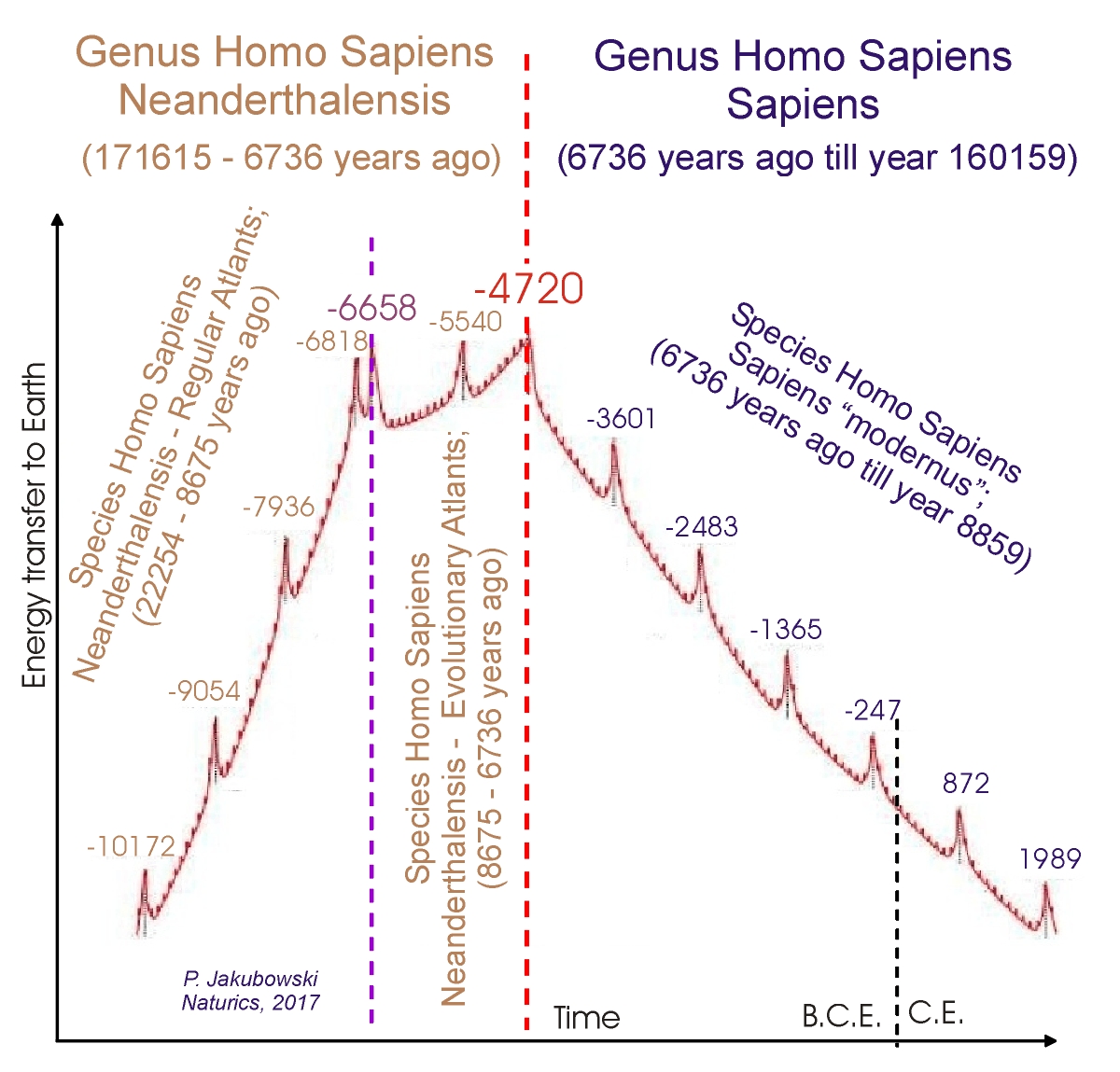

Let's start our analysis by recalling the facts about the life of humanity during the last 12,000 years. The period of the Neanderthal Genus lasted from about 170 thousand years BC until the last quantum leap of the Cosmic Hierarchy of Level 5, which significantly dominated the last 12 thousand years.

The energetic phases of the last jump of level 5 are illustrated in the diagram below.

In the previous article [ UP37. The greatest catastrophe of humanity.], I reported on why the life of the penultimate Species of Neanderthals (to which the Cro Magnon people in Europe also belonged) could still be classified as paradisiacal, while the life of the last (completed) Species of the Regular Atlants had to end in a level 4 catastrophe (6658 BCE). Between such great events, as the establishment of the enormous cult place Göbekli Tepe (12 thousand years ago) and the beginning of the Old-Egyptian culture (3600 v. Chr.) there is a so far inexplicable gap, almost vacuum, in the history of mankind. What happened on Earth between these two time markers? My answer is unequivocal. Regardless of what has not yet been discovered in the details, the events that we can already describe were so traumatising that all people living during this period were affected, and this continued for several dozen generations. People lost control over their own lives, they became speechless; and the events themselves became taboo. The collectively silenced trauma could not be processed as a result. The enormous length of the split period has even caused the ‘new’ humans (of our own Species) to forget and lose their direct connection to their own ancestors (the Neanderthals).

Question 2: What is at the core of PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder)?

The tabooing of highly dramatic events leads to a collective ‘speechlessness’ about what happened. And when the veil of silence is held over something for several centuries, the facts become myths, then fairy tales, and then they disappear from the collective memory. However, the aggressive, mistrust-laden coexistence caused by the dramatic events remains, because the trauma itself is no longer perceived, not recognised as a remnant of those events.

Question 3: What new therapeutic tools does narrative exposure therapy use?

The need to tell a trusted person about a misfortune or even just a mishap that has befallen us is a universal human feeling. And vice versa, the need to help a person who has had an accident by paying attention to their story is also a thoroughly human feeling.

Question 4: How can we ultimately overcome our collective avoidance of the memory of the traumatic events of the last cosmic quantum leap of stage 5?

Even in our case, although we have learned to ‘successfully’ avoid most of our trauma, we have to start talking and thinking about what happened a very long time ago. We have to accept that the new narrative can be as shocking as the dramatic events were back then. We must not try to embellish anything. Possibly up to half of our own ancestors were bandits, criminals (because they were physically and/or mentally crippled). We have only survived to this day because the remaining members of the first Homo sapiens Sapiens found a functional way to defend themselves; by settling down, by domesticating animals and plants, and by socialising their own groups.

Since there can no longer be any contemporary witnesses or relevant documents from this period, a new narrative must be shaped by all competent researchers of ancient times around today's world. I hope that my work will provide an impetus for such cooperation.

Finally, a comment from the authors [Schauer and Bleuel; p.171.], Maggie Schauer and Nataly Bleuel:

‘Because in trauma, every person is alone – isolated. By telling the story, the person is seen. Today we know that attentive and conscious listening promotes health, mindfulness and resilience.’

And another one [Schauer and Bleuel; p.68.]:

‘From the German Academy of Sciences to international research and practice, experts and insiders today agree: just as one should know one's cholesterol level and blood pressure, everyone should also know their (psychological) stress level.’

And for the last time, I will let the authors speak [Schauer and Bleuel; p.113.]:

‘Studying psychological trauma means bearing witness to horrific events.’

I feel warned, but nevertheless, that is exactly what I intend to do. To study the horrific events that accompanied our birth as a Species, even more deeply than before. And to tell this story to everyone, because it is our collective story.

=====

Appendix

Maggie Schauer and Nataly Bleuel provide an answer that is relevant to Question 1 [Schauer and Bleuel; p.236.]:

‘The silence, the individual avoidance as an attempt to prevent contact with traumatic memories, resonates in traumatised communities and leads to a taboo (on the traumatic event). The resulting collective avoidance maintains a fragmented, untruthful false memory of trauma in the community, making a common narrative and reappraisal of the group's history impossible.

The lack of collective memory also fosters distorted and ambiguous truths and fuels fears. It mobilises mistrust and aggression based on selective information because the sense of security has been lost.’

The relevant answer [Schauer and Bleuel; p.39.] by Maggie Schauer and Nataly Bleuel to question 2 is:

‘The core of trauma (is) a memory disorder that keeps those affected in the stranglehold of fear. And that is a taboo. Perhaps the most powerful taboo of humanity - if violence and terror are not allowed to be spoken about, especially not about the manifold consequences of “ordinary” situations because they are more common. ... It is time to understand how important it is to enable narration – that is, narrative penetration of traumatic experiences – and to apply the findings of science to helpful approaches to traumatisation in order to overcome the consequences that are harmful to health and society.’

The relevant answer [Schauer and Bleuel; p.232.] by Maggie Schauer and Nataly Bleuel to question 3 is:

‘The starting point for any trauma support measure must always be to anticipate the avoidance behaviour of those affected. Because when trauma is involved, we can safely assume avoidance. Traumatised individuals and their communities are held captive by their own collective avoidance. The stigmatisation of victims leads to silence and distancing from each other. Traumatised communities need tools to break their own silence. By transforming individual stories into shared knowledge, collective silence is transformed into shared renewal. The seemingly unspeakable can be addressed through the accurate accounts of individuals. Gaps created by suppressed truths are closed and the shared history of pain can be directed towards a shared peaceful future. A process is set in motion.’

And yet another tool [Schauer and Bleuel; p.230.]:

‘To break the cycle of violence, a strong narrative is needed. An arc of understanding that opens up to society and brings decision-makers closer to the meaning of trauma. NETfacts can teach us how to use narratives to convert avoidance into rapprochement, collectively. In NETfacts, communities are presented with the anonymised stories of trauma survivors. The feedback of the narratives to the group has an amazing effect: it maximises public engagement through clinical work combined with cultural practice.’

The authors also provide a relevant answer to question 4 (in several parts):

‘We maintain that there is no person who becomes seriously violent without having experienced violence themselves; and the probability of becoming violent is particularly high if this happened in childhood.’[Schauer and Bleuel; p.232.]

‘It is important to understand that the willingness to use violence usually comes from two sources. On the one hand, reactive aggression, that is, the relieving feeling of overcoming a threat by defending oneself, and, on the other hand, appetitive aggression, that is, the intrinsic pleasure and hunting experience just described, which most former fighters describe as a positive feeling. Once the inhibition to kill has been overcome, many fighters or gang members told us, then the eagerness to hunt and the lust for killing arise, usually in a competing group. In evolutionary terms, this is an old inheritance.[Schauer and Bleuel; p.235.]

‘Therapists should be aware of their own emotions in this regard. When working with survivors, it is important to recognise transference phenomena and to understand that the survivor is trying to regain the control that they lost during the traumatic event. Telling one's life story is therefore a valuable relationship opportunity to reflect on important questions ... What are my life priorities for the coming years? What do I want to focus on? What mark have I made on the world?’[Schauer and Bleuel; p.219.]

‘As a result of traumatic stress, individuals may develop a distorted image of themselves and their past. Aggressive, neglectful, and reality-distorting communication can contribute to the development of various forms of psychopathology throughout life. Some or even all aspects of a person's original experience can be negated and confused (e.g. in the case of developmental trauma), as can thoughts about sensations, emotions, physical reactions and the meaning behind it all."[Schauer and Bleuel; p.189.]