Harald Meller, a prominent archaeologist, Kai Michel, a historian, and Carel van Schaik, an evolutionary biologist, have jointly written 2024 an important scientific document in the form of a book (in German); (‘The Evolution of Violence: Why We Want Peace but Fight Wars: A Human History’; dtv 2024). Below, I quote (mostly without comment) numerous excerpts from this book to explain the topic of my article (‘The Evolution of Violence’) from a scientific perspective.

(p. 11) “At regular mega-conferences, accompanied by enormous media interest, the global community is taking major steps to implement a unified climate policy. Why is nothing comparable being done to eradicate organised killing? Why does the idea that war is inevitable still persist?”

(p. 18) "We do not present a history of war full of gunpowder smoke and the din of battle. The aim of our book is evolutionary enlightenment: based on the current state of research and our own work, we present an analysis of the prehistory of war. We want to uncover the evolutionary roots of aggression and violence and trace their proliferation throughout human history. This allows us to understand the conditions under which war breaks out and who the real warmongers are. Only a correct diagnosis opens up the possibility of developing effective therapies and functioning prevention measures – without appearing politically naive.”

(p. 47) “Important steps in evolution are usually due to climate change. 2.5 million years ago, the climate became drier. The forests and wooded landscapes shrank, as did the wetlands where the hominins of the genus Australopithecus spent most of their time searching for food. ... Although our ancestors were able to cover long distances and do so at a steady trot, they were not high-speed sprinters who could catch prey.

The secret of their success lay in their ability to cooperate effectively and use their intelligence to invent new tools, as well as strategies for obtaining food and cooperating with each other. Over time, hominins became nomadic hunters and gatherers. This was a completely new way of life that had never existed before in the history of primates."

(p. 52) “The beginnings of Homo sapiens are estimated to date back around 300,000 years ago.”

(p. 53) "How large were the groups and how were they organised? ... The average size of such groups is around 25 individuals. These bands are in turn organised into a network of other familiar groups, and people can move quite easily from one group to another. In good times, these so-called “macro-bands” or “communities” occasionally come together to celebrate festivals, perform rituals and form relationships of all kinds. They speak the same language, so macro-bands constitute an ethnolinguistic unit. Sometimes there is a third level, a loose confederation of allied communities with the same or very similar languages, often tracing their origins back to a common source.”

(p. 107) “This means that among nomadic hunters and gatherers, especially those of the distant past, we do not find any of the things that will be typical of war in settled times: no special weapons of war, no fortifications, no battles, let alone extended campaigns, no permanent occupation of enemy territory, no rape of women, no capture and no enslavement of enemies."

(p. 115) "The implications of the findings from evolutionary biology, primatology and ethnography are enormous: on the one hand, they refute the thesis of a permanent state of war in which human evolution is said to have taken place. Violence and conflict were not unknown in prehistory. But wars did not pose a constant threat, and waging war has therefore not become part of the genetic makeup of Homo sapiens, so that humans are inevitably at its mercy. On the other hand, the approach already observed in animals, especially primates, also applies to humans in conflict situations: individuals decide whether or not to resort to violence on the basis of their vital interests by weighing up the risks and benefits. This often meant avoiding conflict. On balance, it was not worthwhile because the potential gain was too risky or simply too small.”

(p. 132) "Humans do have the disposition to wage war. However, they are not genetically programmed for war. And for most of their evolution, humans have had their aggression under control. These are the consequences that lie in the evolutionary logic reconstructed here. Now we need to examine the extent to which this corresponds to prehistoric reality, traces of which archaeology is bringing to light. And above all, we need to find out when and why things could get so terribly out of hand."

(p. 139) "A remarkable irony of history: if you look for prehistoric evidence of war, murder and manslaughter, you find instead evidence of care and nurturing. Palaeoarchaeological findings testify that humans helped and supported each other; otherwise, many injuries would have been a death sentence. Broken arms or legs could lead to permanent disabilities, but these were overcome thanks to the support of the group. In addition, people understood wound care at an early stage. There is evidence from the fossilised tartar of Neanderthals that they had already experimented with plants containing penicillin. The bones therefore tell the story of a species characterised by solidarity rather than one of war between all individuals."

(p. 153) “In view of the archaeological facts, it must be stated that there is no evidence to suggest that human evolution took place in a permanent state of latent war. We were able to live perfectly well without it for more than half an eternity. Then the world changed.”

(p. 163) “It was only 11,700 years ago, with the Holocene, that the relatively stable warm period in which we still live today began.”

(p. 164) “It was only with the beginning of the Mesolithic period and the stabilisation of the climate 11,700 years ago that violence took on new forms in Europe.”

(p. 165) “Evidence of this can be found not least in something we already encountered in Jebel Sahaba: cemeteries. They are a phenomenon of the new, sedentary life. ... Cemeteries create legitimacy. They are territorial markers.”

(p. 168) "Singh and Glowacki are right about one thing, however, namely that archaeology can only give us a small glimpse of the diversity that once existed and that this distorts our view. The most advanced of the early societies in particular may have been swallowed up by the sea, like the mythical Atlantis. Seacoasts have always offered a wide range of food....

We are dealing here with another factor that is likely to have contributed to the increase in conflicts: climate change has been driving people from their homes for a long time – even 10,000 years ago, people were fleeing their homes. Rising sea levels forced them to seek new places to live, with densely populated coastal regions being particularly affected. For thousands of years, it was possible to walk from the European continent to England and from there via the then non-existent North Sea to Denmark and southern Sweden. Then, around 7,500 years ago, the region known as ‘Doggerland’ finally sank beneath the waves. The people living there had to find a new home elsewhere.”

P.J.'s comment: It was the time of the greatest natural disaster in human history, the Cosmic Leap of Level 5 of the Cosmic Hierarchy of the Solar System. That is why it was really the case that ‘the most advanced of the early societies, such as the mythical Atlantis, were swallowed up by the sea.’ And victims of this catastrophe, such as the inhabitants of Doggerland, barely managed to escape the devastating tsunamis of that time.

(p. 178) "This fits best with the observations presented so far: the first concrete evidence of war-like conflicts can be found after the last ice age among those groups that had begun to settle down because they had turned to fishing and hunting other aquatic animals in the new water-rich world.

According to Helbling, the decisive factor is also ‘dependence on spatially concentrated resources’. ... Thanks to the labour invested, the land is regarded as property. ... It was therefore no longer possible to avoid conflict, but instead people had to be prepared to fight it out. This was also a novelty, as people could now be found. Only this opened up the option of planned raids. Sedentarisation led to a dead end in terms of violence.”

(p. 184) “The concept of property is a cultural innovation that unfolded its true significance with increasing territoriality, but above all with the emergence of sedentarisation. ... The sudden monopolisation of land was an affront, especially as it curtailed the freedom of others."

(p. 186) “Punishing others for an offence is, alongside the impulse to defend oneself, the only narrative that has ever convinced humans to resort to attack. It also explains the enormous vehemence of violence. Those who monopolise resources no longer behave like humans, so why should they be treated as such? ’They're not human!’”

(p. 187) “The invention of private property seems to have been the inspiration for the birth of war.”

Below, the authors of the book describe some striking examples of the latest discoveries made by their colleagues.

(p. 189) "Now, the site called Ohalo II, located on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, is of interest to us for another reason that is essential to our argument. Here we find one of the earliest evidence of the systematic use of cereals such as wild barley and emmer. The beginnings of agriculture go back much further than commonly thought. A group of hunters and gatherers settled on the shores of the Sea of Galilee a good 23,000 years ago. Six huts indicate at least seasonal use. While the last ice age had the north in its grip, the Levant suffered from severe drought. In the Jordan Valley, especially around the Sea of Galilee, however, conditions were paradisiacal, with open, park-like forests. Gazelles, fallow deer and hares, as well as water birds and fish, were on the menu. And then there were the local plants: archaeologists identified well over a hundred different species. A particularly wide variety of nuts, berries and fruits were harvested. A millstone for processing wild grains was also in use. Sufficient food sources were available throughout the year. ... In Ohalo II, we see one of the earliest stationary groups, whose remains were later engulfed by rising lake and sea levels. In fact, the site was only discovered in 1989, when the water level fell several metres below normal after years of persistent drought. ... As far as we can see, however, Ohalo II has never been discussed as evidence of early violence.”

(p. 192) "Evidence of fortifications such as those identified at Tell Maghzaliyah in Iraq is rare. The lack of evidence of fortifications meant that one of the most striking fortifications was long denied any military character: In Jericho, where the Bible tells us that trumpets alone brought down the city walls, there was a 1.80-metre-wide and 3.60-metre-high wall with a round tower nine metres in diameter over 10,000 years ago, eight metres of which are still standing today. ... Nowadays, people tend to regard the walls and tower of Jericho as what they obviously are: monumental defensive architecture, the oldest in the world."

(p. 194) "The challenges of the new way of life are magnified in one of the most wondrous places of the Neolithic period: Catalhöyük, a mega-settlement located on the Konya plateau in central Anatolia. Between 7500 and 6200 BC, it was home to between 4000 and 8000 people. There were no roads, the houses stood wall to wall, and access was via the flat roofs. The egalitarian spirit of hunter-gatherers still prevailed: architecturally, no one rose above the others. ... The inhabitants of Catalhöyük cultivated fields, herded goats and sheep, and grazed cattle. They also hunted and fished. ... For a long time, people puzzled over what led to the collapse of Catalhöyük. Large groups of people are vulnerable, yet this experiment, which was new in human history – thousands of people crowded together in one place – went surprisingly well, lasting over a thousand years."

(p. 196) "After all, the decline of Catalhöyük coincides with the exodus from Anatolia to Europe. ... This is how the new food-producing way of life came to Europe. Archaeogeneticists have impressively proven this in recent years. It was therefore not an innovation made or adopted by European hunters and gatherers, but rather imported by Neolithic migrants. The first farmers from Anatolia brought the entire ‘Neolithic package’ with them: they brought grain, livestock and pottery, but also a whole new seed of violence.

It is astonishing how quickly farmers spread across Europe, settling wherever they found fertile loess and, above all, black earth soils. From the middle of the 6th millennium BC, the Linear Pottery culture, as the first Neolithic culture in Central Europe was called, reached the Börde regions of Germany and the Paris Basin. There is no evidence of conflict during the following 300 years. Although some settlements were surrounded by a ditch, this was more of a boundary than a defensive feature. The peaceful times came to an end in 5200 BC with a significant increase in population and a change in climate that caused drought and crop failures.

Were the same mechanisms at work as in Catalhöyük? Only after a period of prosperity, which led to all the land suitable for early agriculture being occupied, did violence escalate. In fact, archaeologists discovered more and more evidence of war and massacres in the period from 5200 to 4800 BC.”

However, it must also be emphasised here that many of the ‘evidence of war and massacres’ discovered must also relate to the victims of the level 5 natural disaster.

(p. 210) "For the human species, the new way of life was a success, at least in quantitative terms. Qualitatively, however, it was not a success for individuals – quite the contrary. The costs were immense. The new diet was more unbalanced, agriculture was back-breaking work, and then there was the hours spent grinding grain. The skeletons speak for themselves: the early farmers were smaller, less healthy, suffered more frequently from tooth decay and lived shorter lives than their mobile ancestors. As women were particularly involved in these activities, their bodies were even more depleted. This resulted in deficiency diseases, and many did not survive pregnancy and childbirth."

(p. 211) "The clans organised along male lines provided the framework for the transfer, i.e. inheritance, of property to the sons, usually the firstborn, which meant that the resulting differences in wealth increased across generations. We know the possible consequences from ethnography: individual older men with power take two or more wives. Simply because they could afford to and no one stopped them.”

(p. 212) “Social inequality thus goes hand in hand with reproductive inequality. In fact, there was a “Y chromosome bottleneck” during the period from around 5000 BC to the year zero: Compared to the female genome, genetic variance in men declined massively during this period. There were large differences in reproductive success. While the vast majority of women had children, a considerable proportion of men remained childless. How this finding, reconstructed from genetic material, can be reconciled with prehistoric conditions is currently under discussion.”

(p. 213) “This overproduction of elites created enormous potential for violence, as it encouraged young men to gain social status through high-risk endeavours. These are mechanisms that correspond remarkably well to the evolutionary logic already presented. In a martial world, they are culturally reinforced, as the royal road to glory now leads through war.”

(p. 238) "How the first states came into being is a much-debated topic. Once celebrated as a sign of progress and a hallmark of advanced civilisations, the picture is now changing. For historian Charles Tilly, we are dealing with products of organised crime: early states should be understood as victims of robbers who engaged in extortion. ...

Our evolutionary explanations also suggest that humans did not voluntarily choose to live in states. For an egalitarian species such as Homo sapiens, this is a change in social organisation that requires a great deal of explanation. Instead of everyone's voice being heard, the world is now divided into rulers and subjects for a long time to come. Only from an evolutionary perspective does the rupture become truly clear, affecting all areas of life, but most profoundly war and violence: for 99 per cent of human history, individuals more or less made their own decisions; in the last one per cent, others make them for them. Whereas people could previously decide against war, they are now sent to war."

(p. 292) "The difference between 99 per cent of human evolution and the last 1 per cent in civilised states could hardly be greater. It almost seems as if we are dealing with two different species, as if humans had mutated from peaceful bonobos into warlike chimpanzees in a very short time. But that is not the case. These are solely cultural changes – which raises the question with even greater urgency: Why did people put up with this? After all, it was they who were sent to wars that primarily benefited a tiny elite, usually just a few individuals at the top of the state. For the longest time, this process was entirely at the expense of most men, but also of all women. Moreover, it contradicts the egalitarian nature of human beings."

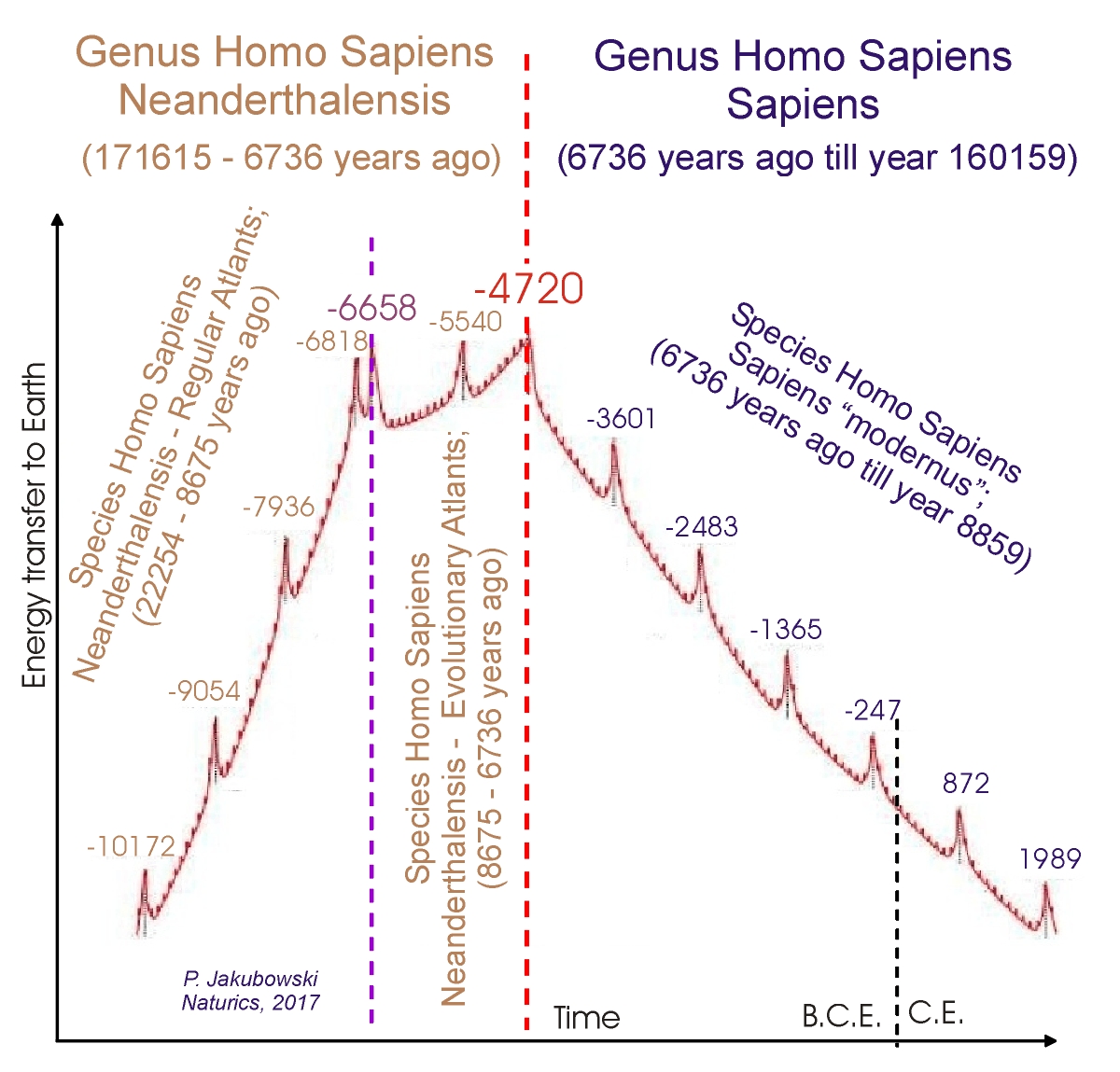

P.J.'s comment: This is the most important point in the entire text of the book: ‘It almost seems as if there were two different species, as if humans had mutated from peaceful bonobos into warlike chimpanzees in a very short time. But that is not the case.’ Yes, it is, that is the case. As our picture of energy supply to Earth over the last 12,000 years shows (see also other articles on this website), it was only the last quantum leap of stage 5 of the Cosmic Hierarchy of our Solar System that ended the lifetime of the Neanderthal species and gave the ‘starting signal’ for the life of our own species, Homo sapiens Sapiens.

(p. 295) "Violence as a means of intimidation may work at the moment a new regime is established. But pure terror is not enough to stabilise power in the long term. It would be a war against one's own population. ... An invisible power is needed that works so imperceptibly that one forgets its existence altogether. ... And that brings us to religion.”

(p. 296) “Like war, religion can only be understood as the cumulative product of biological and cultural evolution – namely, the developments described in this book. Consequently, this is also a complex consisting of various components of different ages and origins. Domination and war play a decisive role in this. They led to a special form of religion. To this day, it presents itself as the only true religion and is closely interwoven with the evolution of violence."

(p. 299) "The anthropologist Stewart Guthrie speaks of “anthropomorphisation”: powerful gods who behave like rulers can only be imagined by humans once they know powerful individuals who have risen to become rulers; gods therefore appear at the earliest in the Neolithic period in the context of hierarchical societies. As a reflection of earthly realities, they are a late phenomenon.”

(p. 300) “In Anatolia, in the heart of the Fertile Crescent, the first monumental architectural structures with temple characteristics can be found in the early days of settled life: the 12,000-year-old Göbekli Tepe is the most famous. Initially attributed to hunter-gatherers, it has become increasingly clear in recent years that their creators were already settled and, as grinding stones prove, systematically used grain. On a hilltop there are five-metre-high stone pillars that seem to represent humans in an abstract way. They are arranged in circles, with benches inside. Not all of these twenty cult circles have been excavated yet. ...

Göbekli Tepe dates back to a time when hunting was losing its importance. Is the ancient world being heroically evoked here to compensate for the loss of this most important source of male prestige? ... Places like Göbekli Tepe belong to a time of intensified ancestor worship ... Without an organising authority, such a monumental programme of images and construction would not have been possible. ... It is obvious that places like Göbekli Tepe are more than just cult sites. Everything points to interpreting them as a primitive form of later temples. ... What took shape at Göbekli Tepe are the beginnings of a religion of violence and domination.”

And here are a few more conclusions from this valuable book:

(p. 322) “That is the predicament we find ourselves in today. Its origins lie in the processes described above, namely the settlement of humans and the invention of intensive agriculture. These led to overpopulation, an insatiable hunger for resources and hyper-consumption, but above all to power-based societies in which states proved to be the most effective war machines. They have left the world with a truly burdensome legacy. States and their borders, the unequal distribution of wealth within and between societies, ethnic and religious tensions – all these are consequences of these processes. People around the world today are grappling with problems whose roots go back many centuries, if not millennia. This makes the problems seem unsolvable – and produces new violence. ... Is peace impossible in a world created by war?"

(p. 329) "So what can we conclude from our explorations of the evolution of violence? First, that there are no simple solutions for reducing violence and war. The aim of this book was to present a diagnosis on the basis of which effective therapies can be developed. This is the task of politics. However, one thing is clear: as terrible as the wars of our time may be, there is no reason for fatalism. Thanks to the findings of many sciences, we now have a solid foundation for making reliable statements about why it is anything but unrealistic to want to reduce collective violence. ... War has become second nature to us. We consider it natural, but it is only a cultural achievement. ... War is naked – it is a scandal.”

(p. 331) “Evolutionary enlightenment robs war of all legitimacy.”

(p. 334) “There is no reason to continue to fear ourselves. It is high time we had the courage to make the world a more humane place.”