In science, it is not primarily about the correct explanation of a problem, but about the right question that draws our attention to the need for an explanation of this problem in the first place. The ability of a scientist to ask the right questions is the necessary prerequisite for the progress that this scientist can make in his field. Hanno Sauer seems to me to be such a gifted scientist in philosophy.

In his book "Moral; Die Erfindung von Gut und Böse; in English: Moral; The Invention of Good and Evil" (Piper, 2023), he poses many of the right questions that need to be asked about the history of the Incarnation in order to be able to tell this story better than before.

On page 23, Hanno Sauer asks:

"But why was social life so important to our ancestors? Why did our ability to co-operate begin to play such an important role?"

And on page 46 he asks even more detailed questions:

"How did evolution manage to generate altruistic or co-operative tendencies, even though these - it seems, at least - necessarily reduce our reproductive fitness? How could it ever be beneficial for me to help another? How could it ever pay off to subordinate my self-interest to the welfare of the community?"

Hanno Sauer naturally also provides his answers to these important questions. On page 59 we read, for example:

"To explain how the astonishing extent of human co-operation became possible, an increasing number of scientists are falling back on the concept of group selection. The idea here is that we humans evolved the ability to co-operate extensively because only groups with hyper-cooperative members could prevail over other groups in the competition for scarce resources in our environment of evolutionary adaptation. ... And it is also true that, although selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals, groups of altruists are superior to groups of selfish individuals."

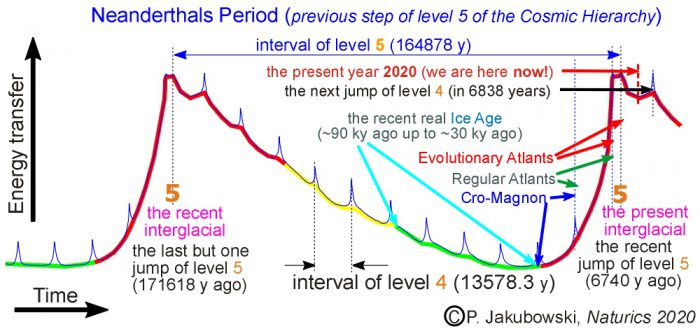

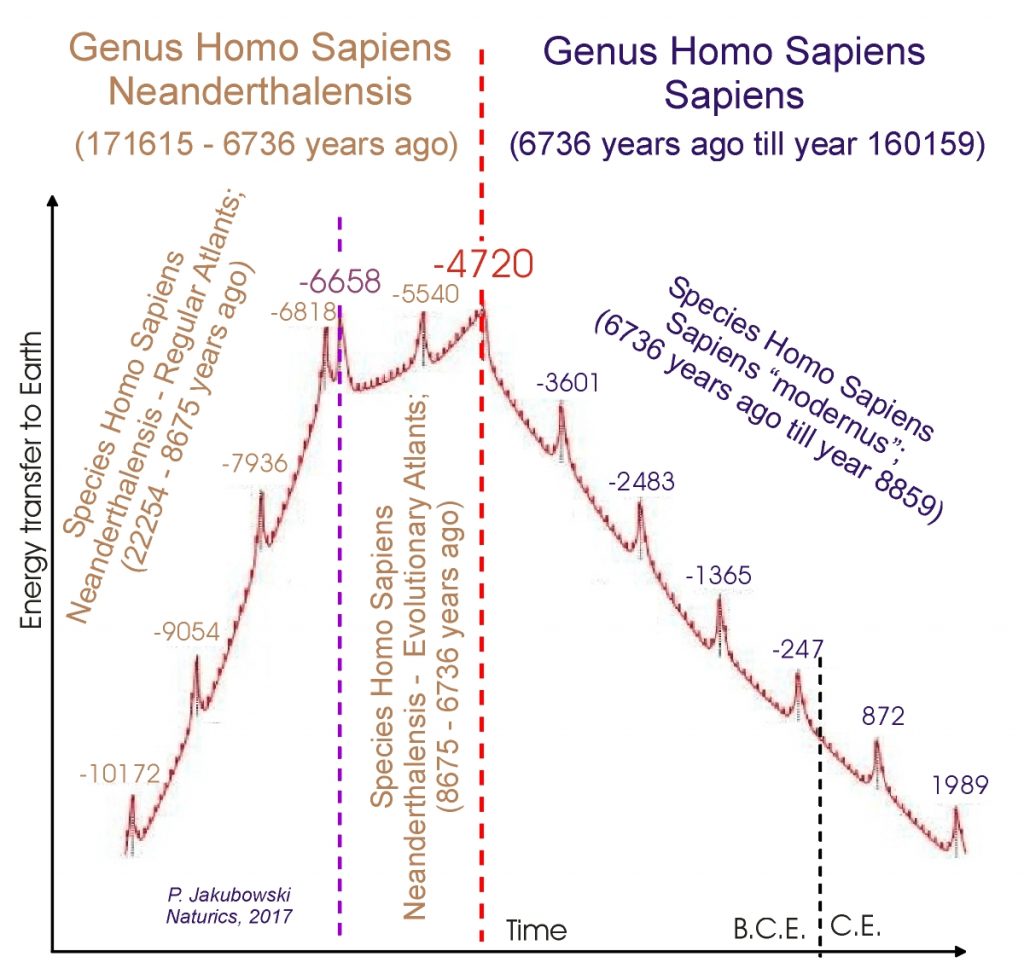

My (P.J.) answer to these important questions can be given in much greater depth and detail because I have at my disposal the unique tool of the Universal Philosophy of Life, the Universal Time Scale. This time scale orders all past periods of the evolution of the Solar System, and of life on our unique planet of this system, along a common scale of non-linear but circulating time in our quantised Universe.

What most, including Hanno Sauer, evolutionary scientists are engaged in is an analysis of a logical chain of possibilities that could have led our common ancestors with the apes to evolve further and further until at some point (an estimated five million years ago) a smarter, or just luckier group, accelerated their evolution while the rest of our "ape kin" got "stuck" in evolution (that is, not exposed to any further urge for improvement). In the words of Hanno Sauer (on page 23), such analysis sounds like this:

"These questions bring us back to the climatic-geological changes that resulted from the Great African Rift Valley. ... The destabilisation of our environment and the fact that we were exposed to dangerous predators on a far more drastic scale increased the pressure to compensate for this new vulnerability by improving mutual protection. We found support and strength in larger groups with closer co-operation. We humans are what the most intelligent apes become when forced to live in open spaces in large grasslands for five million years."

However, the periods of time in our quantised Universe are always finite. After their expiry, there is always an upheaval in the evolution of the Solar System, and thus also in the evolution of life on Earth. Such a cosmic quantum leap of a certain level of the Cosmic Hierarchy of the Solar System (between the highest level 9 and the lowest, cosmically still relevant level 4) practically always means several impacts of the correspondingly large cosmic chunks on the Earth's surface first. The resulting more or less global earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, landslides and forest fires cause a correspondingly deep disruption in the life of fauna and flora, which living organisms ultimately perceive as an environmental catastrophe. Most groups of organisms do not survive such level 9 to 5 environmental disasters. To date, traditional science recognises only five of these so-called "mass extinctions". In reality, according to my Universal Time Scale, since the explosion of life about 550 million years ago, 2 level 8 environmental catastrophes, 22 level 7 environmental catastrophes, 22x12 level 6 environmental catastrophes, and still 12 times more level 5 catastrophes have occurred. The last level 5 environmental catastrophe occurred between 10000 and 6000 years before today (with its peak in 4720 years before the beginning of our current era).

As long as serious evolutionary research does not take these catastrophes, and especially the last of them, into account, we will not be able to answer Hanno Sauer's intelligent questions in a truly intelligent way.

In the last chapter: Conclusion; "The future of everything", on page 330, Hanno Sauer finally asks:

"What happens next? What can we hope for, what must we fear?

The moral crisis of the present is a crisis of divisiveness, or more precisely: of apparent divisiveness. The contradictory dual promise of freedom and equality that modern societies have given us has never been honoured. The frustration and outrage that resulted released the energies of old instincts, dividing the world once again into Us and Them. If we want to overcome this crisis, we need to understand the mechanisms that led to this social division. The clash of identities that defines our present arises from the forces that have always driven the biological, cultural and social evolution of humanity.

The evolution of co-operation explains why our morality is group-oriented. Cooperative behaviour could only prevail because and when it was limited to a small number of people - us - and withheld from others - them. Us and Them arise because only kinship, reciprocal exchange and cooperative behaviour within our narrowly circumscribed group create the conditions under which the benefits of moral behaviour outweigh its costs."

(p.331) "We acquired the ability to orientate ourselves to norms, to monitor and punish their violation. Our group-orientated moral psychology became punitive. ... Shared values and markers of identity created the necessary social trust. Our punitive, group-orientated moral psychology became identity-orientated. In the course of cultural evolution, ever-growing large-scale societies emerged that generated surplus income, which, legitimised by the first ideologies, was organised hierarchically and distributed unequally. Our social world split into small ruling elites and a majority of exploited and oppressed people. It became inegalitarian."

[We put it once more here: All these changes in our moral psychology, however, were mainly forced as a necessity reaction; out of fear of physical annihilation by the numerous wild and crazy (because of the incredible cosmic irradiation) members of our new Genus and Species Homo sapiens Sapiens as a result of the last cosmic quantum leap of stage 5 of our evolution around the year 4720 before the beginning of our modern era].

(p.332) "With the development of modernity, the existing inequalities and moral failures of war, genocide, discrimination and exploitation became increasingly morally intolerable to an enlightened society. The final realisation of the demand for freedom and equality for all became more and more urgent, accelerated by the catastrophic experiences of the 20th century."

[P.J.; But above all through the transition of Level 3 of the Cosmic Hierarchy, whose energy fuelled this evolutionary leap of humanity around the year 1989].

(p.333) "It remains to be seen whether we have the ability to develop values and strategies that are global and resilient in the long term. How can social co-operation be made possible at the level of humanity as a whole, including generations living far into the future? We are facing this task for the first time: we do not know whether we are capable of doing this or whether we have created a world in which we can never be at home again."

[My proposal of participatory family democracy could be a real solution].

Chapter: Introduction; "Everything that was important to us"

(p.12) "Every change has a dialectic, every welcome development has a hard, dark, cold side, every progress has a price. Our early evolution made us co-operative, but also hostile to all who did not belong to our group - whoever says >>we<< soon also says >>they<<; the development of punishment domesticated us, made us friendly and agreeable, but also equipped us with powerful punitive instincts with which we monitored compliance with our rules; our culture gave us new knowledge and new skills which we learnt from others - and thereby made us dependent on these others; the emergence of inequality and domination brought unprecedented wealth and a new level of hierarchy and oppression; modernity unleashed the individual who brought nature under his control with science and technology; in the process we demystified our world, in which we are now homeless, and created the conditions for colonialism and slavery; the 20th century sought to create a peaceful world through global institutions. The 20th century sought to create, through global institutions, a peaceful society in which all enjoy equal moral status, brought us the most breathtaking crimes in human history and manoeuvred us to the brink of ecological collapse; more recently we have been trying to finally shed that legacy of arbitrariness and discrimination, racism and sexism, homophobia and exclusion; it will be worth it, but we will pay some price for it too."

(p.13) "The story I am going to tell wants to make a contribution to understanding the present. ... To understand the present, one must turn to the past. ... An increased need for co-operation due to external environmental changes could only be met by living together in ever larger groups."

Chapter 1; "5,000,000 years; genealogy 2.0"

(p.19) "A shopping trolley half-filled with stone bones. That's all that's left of our earliest ancestors. In any case, nothing more was ever found than a few teeth, skull fragments, fragments of eyebrow ridges, parts of upper and lower jaws, splinters of a few thigh bones."

(p.20) "Finally, the term Hominini includes all humans in the narrower, but still not in the narrowest sense: this tribe - biologically Tribus - includes the earliest human-like (but admittedly not yet very human) beings who began to populate parts of southern and eastern Africa about five million years ago, a number of australopithecines and various more familiar categories such as Homo ergaster, erectus, heidelbergensis and neanderthalensis. Of these hominins, only we remain today: Homo sapiens."

(p.21) "Access to our deepest past always remains speculative, but not in the nebulous sense of the unverifiable and hair-pulling, but in the solid sense in which legions of clever minds, armed with the most cunning methods of comparative morphology, molecular genetics, radiocarbon dating, biochemistry, statistics and geology, attempt to reconstruct the most plausible version of this history from many heterogeneous theories and data sets."

[Our Universal Time Scale is the best, and even the necessary, tool for this].

(p.23) "But why was social life so important to our ancestors? Why did our ability to co-operate begin to play such an important role? These questions bring us back to the climatic-geological changes brought about by the Great Rift Valley. ...

The destabilisation of our environment and the fact that we were exposed to dangerous predators on a much more drastic scale increased the pressure to compensate for this new vulnerability by improving mutual protection. We found support and strength in larger groups with closer co-operation. We humans are what the most intelligent apes become when forced to live in open spaces in large grasslands for five million years."

[But our ancestors were especially lucky to have come up with the idea of "defence by fire"! These lucky gorillas became Australopithecines 4.3 million years ago, smaller but smarter].

(p.29) "The increasing scale of a community has a destabilising effect in the long run because we inherently lack the institutional toolkit to make cooperative arrangements resilient in the long run. (Robin) Dunbar (the British evolutionary psychologist) is even of the opinion that the natural group size of human populations, derived from their average cerebral volume, can be narrowed down relatively precisely to 150 people. This value can be found in a wide variety of contexts, from tribal societies to the internal structure of military organisations. To put it bluntly, there are at most 150 people that you would be comfortable joining for a drink in a bar. The special thing about human societies is, of course, that they can integrate far more than 150 people. However, this has only recently become possible and not without an institutional framework that regulates the formation of larger groups in a co-operative manner. Spontaneous communities split up as soon as their numerical capacity is overstretched."

(p.45) "A modern, scientifically founded genealogy of morality must therefore explain one thing above all: How have we humans managed to develop co-operative dispositions even though they are evolutionarily unstable? To answer this question, we need to take a closer look at the conditions under which we had to master this evolutionary challenge."

[This is a false question. Individual families have already begun to do so. The right question is: When and why did we lose these co-operative dispositions? The answer is: during the several-thousand-year-long transition period of the last cosmic leap of level 5, so many "good" people were killed by their "bad" fellow human beings that the co-operation of larger groups became necessary to ensure common protection. But this happened much (more than four million years) later than the transition from gorillas to australopithecines].

(p.46) "How did evolution manage to produce altruistic or co-operative tendencies when these - it seems at least - necessarily reduce our reproductive fitness? How could it ever be beneficial for me to help another? How could it ever pay to subordinate my self-interest to the welfare of the community?"

[For fear of extinction! Only the clever "scaredy-cats" survived].

(p.59) "To explain how the astonishing degree of human co-operation became possible, an increasing number of scientists are resorting to the concept of group selection. The idea here is that we humans have evolved the ability to co-operate extensively because only groups with hyper-cooperative members have been able to outcompete other groups in our environment of evolutionary adaptation for scarce resources. ... And it is also true that, although selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals, groups of altruists are superior to groups of selfish individuals."

[The first trigger was simply the fear of survival. The co-operative ones survived the last cosmic quantum leap of level 5 best, or successfully at all].

Chapter 4; "5000 Years; The Invention of Inequality"

(p.145) "Every culture recognises the idea of a golden age. ... Myths are always untrue, but often not entirely. It is now becoming increasingly apparent that man's original way of life may have been remarkably more tolerable. True, there was no penicillin, no dentistry and no taxis, but there were also hardly any infectious diseases, periodontal disease or inconvenient appointments. Above all, the age between the separation of humans from their closest relatives primates (a few million years ago) and the emergence of the first complex societies (a few thousand years ago) seems to have been characterised by an astonishing degree of political, material and social equality."

(p.148) "It is puzzling why we ever left our Golden Age of Equality. What led to the discovery of inequality 5000 years ago?"

[The cosmic quantum leap of level 5 has forced humanity to make this corresponding evolutionary leap from the species Homo sapiens Neanderthalensis to our species Homo sapiens Sapiens. Only with the help of the last Neanderthals did we make this leap].

(p.149) "Nevertheless, it is now almost universally agreed that simple, often nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers were almost always organised in an astonishingly egalitarian way. ...

One of the main factors in the transition process to hierarchy and inequality appears to have been the development of an increasingly sedentary lifestyle and agriculture. With the end of the Ice Age about 10,000 years ago - after a period of instability lasting many hundreds of thousands of years, which made us intelligent and capable of learning - the climatic conditions arose for the first time to successfully practise agriculture, keep livestock and cultivate plants. ...

Are we humans better off since we left our stateless primitive state? Or is the transition from tribe to state really the root of all evil?"

[The answer to the last question is: decidedly: yes! But we had no choice. We had to go this way in order to survive as a species. We became sedentary, and we domesticated farm animals and plants, not out of the urge to progress, but out of fear; out of fear of our mentally and physically savage fellow human beings, who had seen the light of day as cosmically irradiated "freaks" during and after the catastrophe. But now, because we have finally understood all this, we are in a position to put an end to all this evil and to make a new Golden Age possible for our descendants].

(p.183) "The problem of social inequality arose in the early civilisations of the ancient world. For the last 5,000 years, there has always been no question that there are a few who have power and wealth, while the overwhelming majority remain poor and disenfranchised. It is only recently that the question of the basic principles of a just society has been addressed anew and with unprecedented urgency. What does a society that recognises the dignity of the individual look like? How can we reconcile the freedom of the individual with the desire for earthly happiness? And what does it mean to live among equals?"

[Exactly the right questions; I gave my answers here above].